Before I get started, an apology. When I started this newsletter, I fully expected to be able to post at least once a week, perhaps more, but I had underestimated two things – firstly, what happens to my workload at certain times of the year. As a freelancer, I find myself programmed not to turn down work. This is usually manageable but an unavoidable change in deadlines last month meant that I had a few mad weeks working on three projects at once and absolutely no headspace. Next time it happens – and it will happen again, freelancing can be very boom/bust – I shall try to anticipate better and either have stuff prepared in advance or (to be more realistic about it), announce a hiatus. Which will be much better than self-flagellation over lack of delivery…

The second thing I underestimated was how long it can take me to write these posts. As I’ve mentioned before, deciding on the subject matter is very organic – they usually come about because of a thought triggered when writing about something else. They then take quite a lot of thinking time – and often some testing too. I can’t just sit down and write them, they percolate for weeks beforehand. I have always written like this. I think, think, think, have a couple of false starts then suddenly it is ready to come out, and does. No pun intended but it is like a pressure release.

So the thorny subject of pressure cooking and liquid levels has been on my mind for a while. It is probably the aspect of pressure cooking I am asked about the most. The reason for this is that the manufacturers specify minimum amounts of liquids necessary for pressure cooking and a lot of my recipes require a lot less. This confuses, I know. I have had people describe how they have followed one of my recipes, worked out how much more water/liquid they need to add to make up the minimum specified by the manual and then wonder why they are constantly making runny, water logged food.

So I do appreciate that a lot of you are very nervous about trusting my liquid levels – and I know that some of you who have been using my recipes for years are tempted to add more than specified. Some of you have even asked me if a pressure cooker is more likely to explode if a below minimum amount of liquid is used. No! The worst thing that can happen is that it boils dry, just as a saucepan might.

Why the discrepancy? And why is it important? Well, firstly importance – why use more liquid than you need? Less liquid means that your pressure cooker will come up to pressure faster so you save more in terms of time, fuel, money and of course water. But also it means that you don’t have to discard or reduce liquid after you have cooked at pressure.

And why the discrepancy? I don’t know why the manufacturers give these minimum levels, but I do have my theories. I think it is possible that it is a hangover from when manuals were written for old style pressure cookers. These are more likely to give out steam while cooking at pressure so if you are cooking something for a long period of time (eg., a Christmas pudding), you would traditionally need more water. Not so with modern pressure cookers as they shouldn’t give out steam whilst cooking at pressure. Although the manuals can get this wrong as well. One pressure cooker manual I own says that the cooker is cooking at pressure when it is letting out a steady stream of steam. This is absolutely wrong, at this point the cooker is cooking over pressure.

So – to recap, back in the day, when pressure cookers belched out steam when they cooked at pressure, minimum levels of liquid were given and of course the longer the cooking time, the more liquid was necessary. And this is still the case with whistling pressure cookers although these also give out much less steam than you think. These days pressure cookers are designed to let out minimal amounts of steam – or for the super duper efficient ones, none at all. So really, the main question becomes how much water is necessary to bring a pressure cooker up to pressure, as it should be a given that the same amount of liquid should create enough steam to maintain that pressure pretty much indefinitely.

I’m not sure exactly when I started experimenting with this, but it was quite early on when I was trying to push the boundaries of the – at the time – accepted limitations of pressure cooking. I won’t tell you about some of the things I tried, as they were stupid and frankly dangerous, but regarding liquid levels – I suspect I was getting frustrated by having to braise vegetables in a minimum amount of liquid if I wanted to not steam them. (And because of my experiments with liquid levels I rarely bother to steam these days, as it is slower and I can’t be bothered to find my trivets and steamer baskets which are often in a drawer and buried under a pile of kitchen detritus the size of Jardim Gramacho). And it went from there.

This was years ago when I was writing my first pressure cooker cookbook and I have kept liquid levels to an absolute minimum ever since. But this week I thought it might be useful to do some proper water tests (ie, no food in the cooker). I used a variety of sizes as of course the amount of steam needed – and water needed to create the steam - is dependent on the size of the cavity it has to fill. In theory, less water should be needed for running the same tests with food – because food takes up space and also gives out liquid as it cooks. So you can take it that for anything up to 6 litres, these amounts should work with anything you are cooking, as long as it is the type of food that gives out water when it is cooked as opposed to absorbing it (mainly dried beans, pulses and grains).

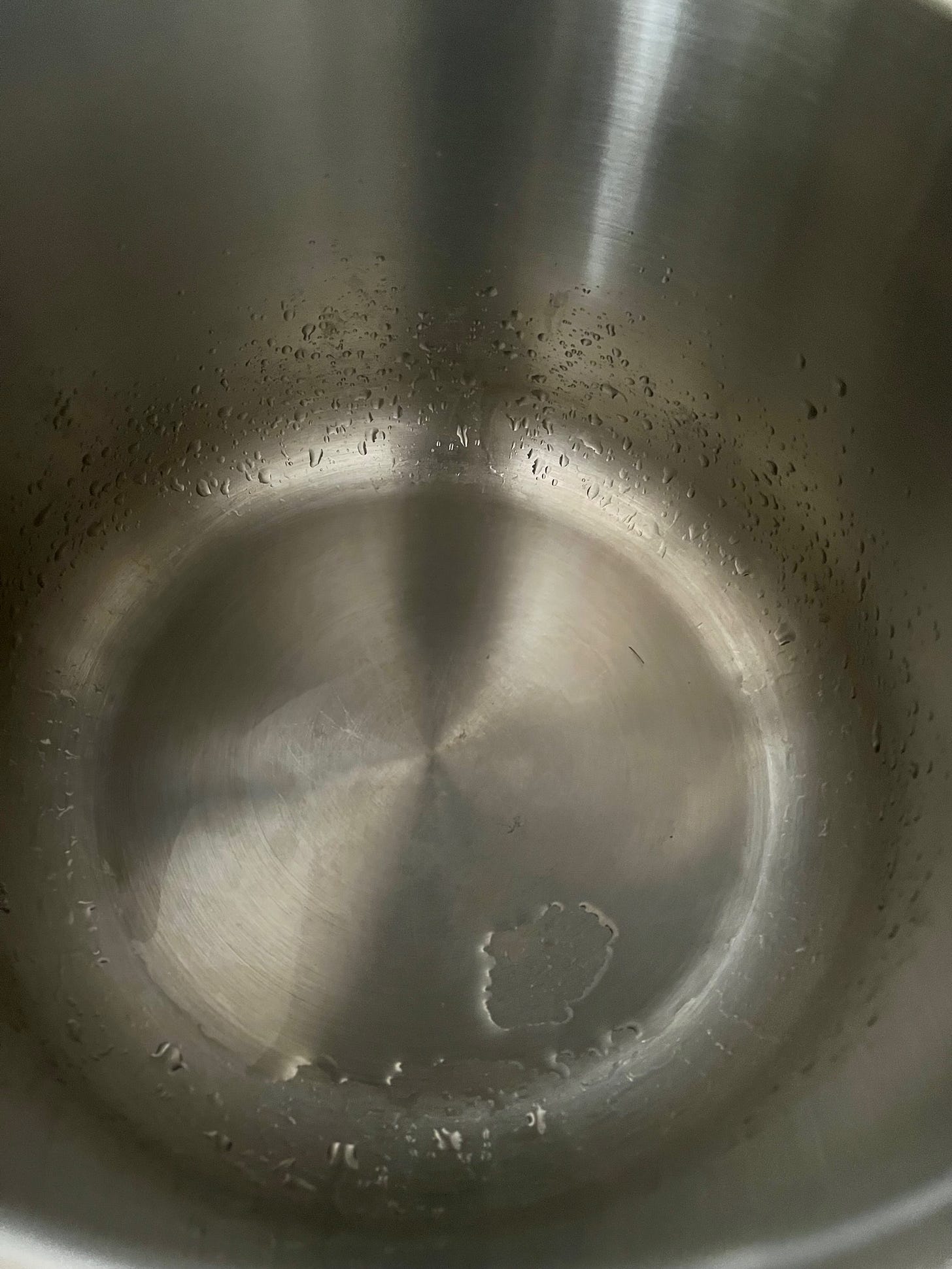

I have tested this on a range of stove top pressure cookers (Kuhn Rikon, WMF, ProCook and Figor, not my Tower as it is on loan elsewhere), up to a 6 litre capacity. And I also tried it in the Instant Pot which is the only electric pressure cooker I currently own. I put amounts of cold water in the base of the cookers, brought them up to pressure and maintained pressure for 5 minutes followed by a natural release. In every case I was able to do this with just 25ml of water. They all came up to pressure remarkably quickly considering the water was cold – between 30 and 90 seconds, even the Instant Pot – and maintained the pressure without any issue at all.

I admit, I was surprised by this. I often cook green vegetables with no or just a merest splash of added water – but they are usually wet from washing (I give a cursory shake). Plus as they are in the pot, taking up room, less steam is necessary. I was also quite surprised how fast the cookers came up to pressure – again, when I cook vegetables I am used to the cooker coming up to pressure fast – almost immediately – when there is already a lot of steam in the pot, but from cold? With a large cavity to fill with steam? And in most cases on a not particularly efficient gas hob? I was impressed.

I haven’t experimented below 25ml, because I don’t really see the point – any food in the cooker which is cooked with minimum liquid is going to give out easily that amount of liquid in steam as it heats. And actually, I do wonder whether this is something else the manufacturers haven’t taken into account - when you cook food, it generally gives out moisture by way of steam. This is especially true of fruit and certain vegetables of course, but also think about how much shrinkage there is on meat when you cook it. As you are pressure cooking in a sealed vessel, any liquid which comes out of your food is just going to combine with the liquid which will condense back down from steam – which is why you usually find more liquid in your pot at the end of cooking than you do at the start.

I know this is a longwinded way of asking you to please trust my recipes! And to further this, I do recommend you try these water tests if you are at all nervous. You can start at the manufacturer’s recommended minimum and work down if it makes you feel better. As long your pressure cooker is working properly and you put it on a high heat while you bring it up to pressure, you shouldn’t have any issues and it might help you feel more comfortable about the low liquid recipes.

I’m going to talk more about liquid levels in my next post but more in the context of actual food and recipes. I find that I have mentally categorised various types of pressure cooking with liquid levels in mind and it has definitely informed how I develop recipes and cook. I hope you’ll find it useful.

I had a few “burn” incidents with my instant pot that made me wary about not adding enough water. But I think that may be more about certain ingredients such as coconut milk sinking to the bottom than lack of liquid. This Madhur Jaffrey recipe which has no water added at all has never failed me and convinced me that less was more regarding water in the pressure cooker. Now I tend to reduce the amount of liquid suggested in most pressure cooker recipes, except yours of course Catherine!

https://www.lovefood.com/recipes/59901/lamb-browned-in-its-sauce-recipe

Thanks very much for doing the research - adding sufficient water has been a concern as I’ve dared to become a bit more creative, so this is perfect. And you are correct, my fear stems from an old Prestige where you were instructed to have a stream of steam.